Cloud computing: the evolution of virtualization

Published on September 9, 2015

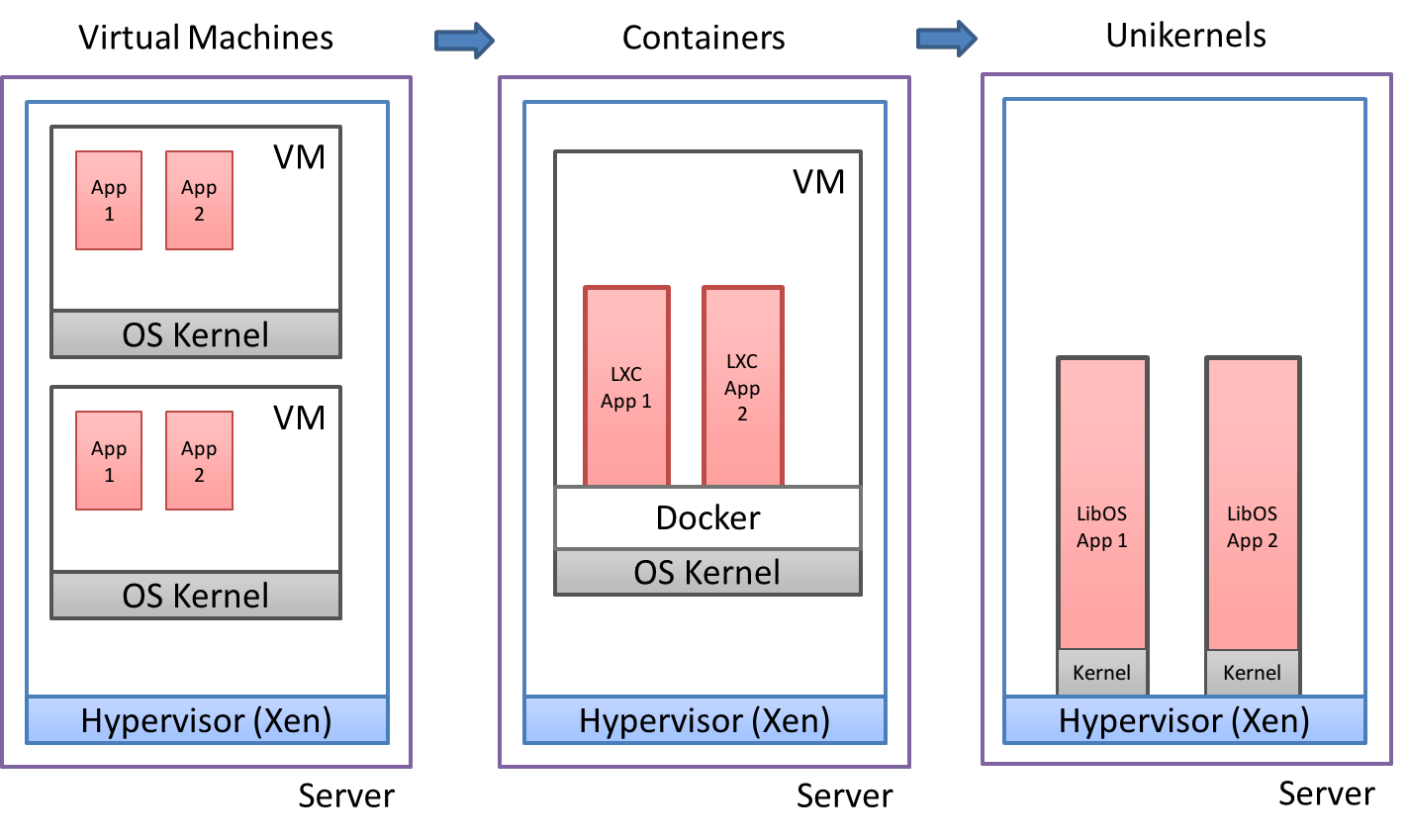

Cloud computing is a fast evolving area, and lines are currently moving. In particular, the Cloud computing paradigm is adding a lot of new layers of abstraction on top of the traditional computing stack: IaaS, PaaS, SaaS… Those new layers are actually making the already existing layers and boundaries less useful. That’s why we are evolving from the legacy-heavy VMs to the very light Unikernels (also called libOS):

The VMs

In the current IaaS implementation, several VMs are running on top of an hypervisor, as shown in the figure. Those VMs embed a complete Operating System (in grey in the figure, for example Windows or Linux). In turn, those VMs can run many applications (in red in the figure). But those VMs OSes were not historically made for the Cloud: they where made for standalone PCs or servers, with features such as multiusers, multiapplications and multithreading. However now, those features appear to be redundant with the hypervisor: the hypervisor is already providing isolation between application and resource scheduling between the various VMs. The VM OSes also embeds thousands of useless drivers. When the concept of Operating System was created, it was its purpose to abstract out the hardware from the software running on it. As such, the OSes needed to embed drivers for practically all existing hardware. Furthermore, each VM on a server embeds its own kernel (the core of the OS), and a modern server can host up to 50 VMs. This is showing a high level of redundancy: multiple kernels are colocated on the same server.

The containers

In order to remove part of the above redundancies, recent trends are seeing increasing adoption of container technologies, such as Docker and LXC. Instead of creating a full virtual machine on top of the host OS, containers use OS APIs to create separate environments (the containers), each with their own file system, memory space and processes. For the sake of multitenancy, containers on the same machine are isolated from each other, but they all share the same kernel. This means that the amount of replicated resources for each container on the same machine is greatly reduced with respect to virtual machines, which implies smaller footprint, higher per-host density and faster start times. Also, containers can be run on bare metal without the need for an hypervisor, thus removing a layer of abstraction and improving performance. This feature also makes them an optimal choice for multitenancy on micro servers which do not support virtualization.

As a downside, since there is only one kernel running per physical machine, it is not possible to mix containers requiring different underlying OSes such as Windows and Linux on the same host. Furthermore, since all containers have access to a broad range of system APIs on the same kernel, the attack surface for malicious users is increased. In fact, an attacker could use an application running in a container to exploit a kernel vulnerability and therefore gain access to all other containers running on the same machine. In a virtual machine, the attacker would still be confined to its own instance by the hypervisor.

The Unikernel

The next, ultimate step in this progression is the Unikernel. A Unikernel is an application compiled together with a so-called “Library OS”. The result of this compilation is not an executable than should run on top of an OS: it is itself an OS. The compiled Unikernel runs directly on Xen. As such, Unikernels can be viewed as single-purpose barebone VMs. The advantages of this technology are multiple:

- Extremely reduced size (a Unikernel can be in the order of magnitude of 10Mo, where a VM is 1Go), due to the elimination of many redundancies.

- Fast bootup speed: the Unikernel being singlepurpose, it has a very reduced kernel with no useless drivers.

- Security: a reduced attack surface, due to its small size and elimination of useless drivers.

- Reliability: Unikernels are traditionally based on the functional programming paradigm, which is known to produce more reliable programs (i.e. with less bugs).