Transporting heavy things (the wrong way)

An interesting geometry problem

Published on October 15, 2023

Wow, a math post, it’s been a long time! Last one was 9 years ago.

Intro

Here an intro, tiktok style (click for video):

I want to strap down a big heavy cylinder on a flatbed truck.

The strap is attached to the truck bed as shown in the picture and also behind.

Will the strap slip off as in the next picture?

For very flat cylinders (close to a circle), the rope cannot slip: the rope is following a diameter of the circle and it’s obviously the shorter path from one side to the other. Try with a plate!

However, for higher cylinders (like the glass in my video), it tends to slip.

Model

We can model the position of the string as in figure below (where I omitted for clarity the lateral surface of the cylinder): its initial position is along path \(ABCD\), but we can study what happens if it follows a slightly displaced path \(AEFD\), where \(AE\) and \(DF\) are geodesic on the cylinder, i.e. straight lines on its unfolding.

If we set \(h=AB=CD\), \(r=BO=OC\) and \(\alpha=\angle BOE\), then the length \(l\) of \(AEFD\) is: \[ l(\alpha)=2\sqrt{h^2+r^2\alpha^2}+2r\cos\alpha. \] (Note that \(BE=r\alpha\) and that \(ABE\) is a right triangle on the unfolded cylinder).

Visual resolution

Say that you are pulling the top strap sideways so that it stays parallel to its initial position. As you pull, the top part of the cylinder will “produce” slack because a chord of the circle is always shorter than the diameter. In the same time, the side will “consume” slack because the strap is now oblique instead of vertical. Which one wins?

Using the notation above with \(r = 1\) and \(h = 1\), the top section will produce slack similar to a cosine (horizontal axis is the angle \(\alpha\), vertical is the amount of “slack” given): \[ 1-\cos\alpha \]

The side will consume slack proportional to (horizontal axis is the angle \(\alpha\), vertical is the amount of “slack” consummed): \[ \sqrt {1 + \alpha^2 }-1 \]

Those two functions looks very similar. Here they are on the same graph.

Zooming in, the blue curve is always above the green curve (on the range \(0<\alpha<\pi/2)\), so theoretically for \(h=r\) it will slip.

Here is a 3D plot with \(\alpha\) on the x axis and h on the y axis (\(r=1\)). Vertically is the amount of slack in total (top - side).

From this plot we can see that for \(h<1\), the surface dips below 0 (blue/purple part). More slack is taken than given: it holds tight. For \(h>1\), the surface is above 0 (green part): it slips.

Numerical resolution

Let’s call \(s\) the slack.

\[ s(\alpha) = 1 -\cos\alpha - \sqrt {h^2 + \alpha^2 } + h \]

We have no slack at the start: \(s(0)=0\). Around this point, we need to calculate the derivate of \(s(\alpha)\) to know if the slack will increase or decrease.

\[ s'(\alpha) = \sin\alpha - \frac{\alpha} {\sqrt {h^2 + \alpha^2} } \]

We have \(s'(0)=0\) (if \(h>0\)), which means that the slack varies very little around \(\alpha=0\). There is as much slack consumed than slack produced.

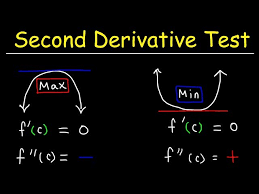

To see if \(\alpha=0\) is a point of minimum or maximum, we can compute the second derivative: \[ s''(\alpha) = \cos\left(x\right)-\dfrac{y^2}{\left(x^2+y^2\right)^\frac{3}{2}} \]

\[ s''(0)= 1 - \dfrac{1}{h} \]

Remember:

For \(h<1\), the second derivative is negative. This means that the slack is at its a minimum! The slack will slowly increase. It slips.

For \(h>1\), the second derivative is positive. This means that the slack is at its a maximum already and will become “negative” is you pull the string. It holds tight.

Looking closer

Some part of the surface above looks funny. Here it is with \(h=0.9\) (slightly shorted than the radius):

The curve dips below 0 before getting back up. This shape is normally safe (\(h<1\)), however if the strap is even slightly elastic or you misplace it, it can reach a point were it will completely slip off.

Shapes below \(h=0.74\) are completely safe:

The curve never gets above 0 before \(\pi/2\). You can strap them as you want (even close to the border): they will not slip.

Conclusion

The strap will slip is the cylinder is higher than its radius. If the cylinder is flater, it will stay on. However, for cylinder that are very close to h = r (same height than the radius), it is dangerous: if you misplace the strap just slightly, it will start to slip and eventually fall off completely!